Dr. Hasan Jeffries discusses hip hop’s history of politics and speaking out

Jan 24, 2023

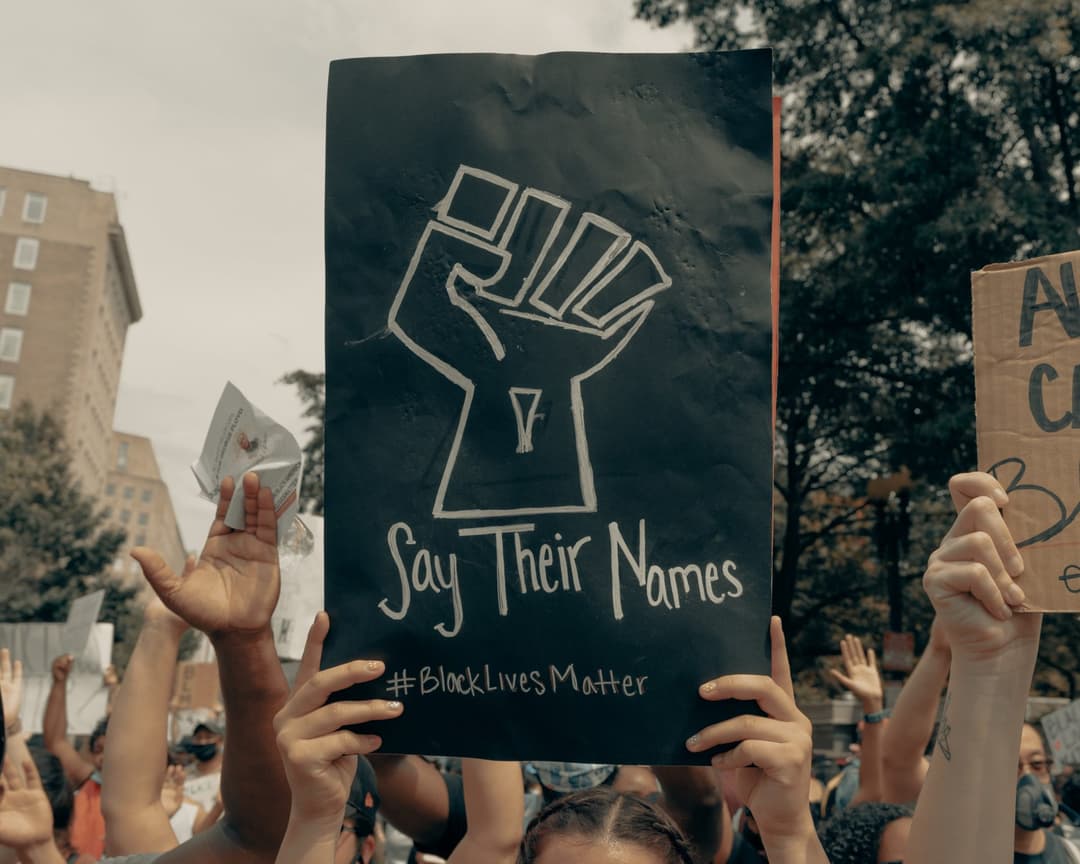

Hip hop turns 50 this year, and the new PBS documentary “Fight the Power: How Hip Hop Changed the World,” executive produced by Chuck D of Public Enemy, chronicles the history of the art form that reflects the emotions, expressions and experiences of the nation’s Black and brown communities.

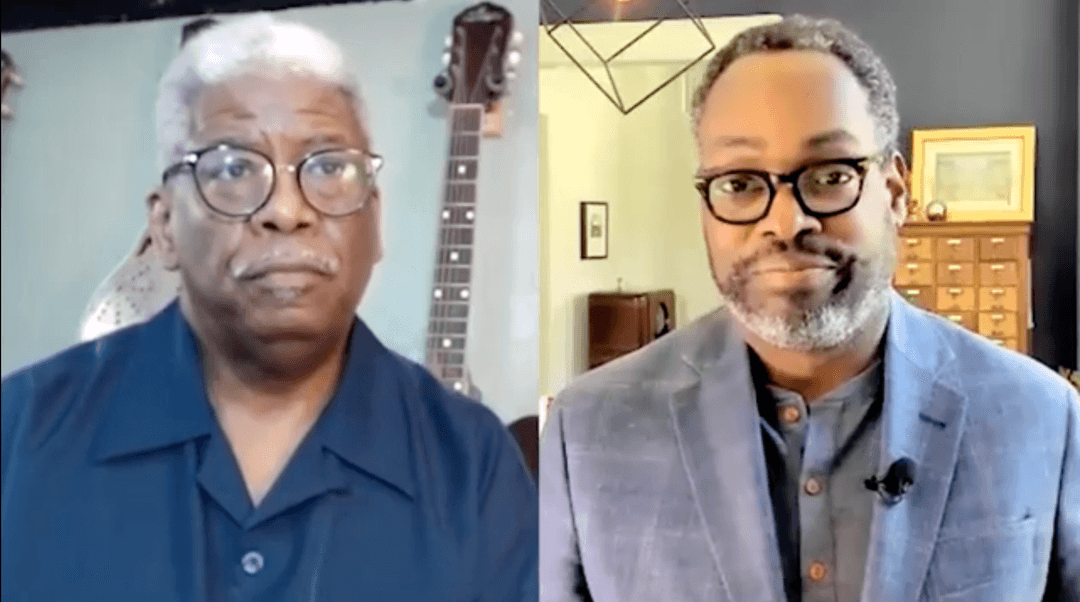

To celebrate the historic milestone, “American Black Journal” host Stephen Henderson sits down with Dr. Hasan Jeffries, an associate professor of history at The Ohio State University, to learn about his participation in the “Fight the Power” documentary. They also talk about the history of hip hop’s political messages, and how artists use the genre to speak out and express opposition to what’s going on in society and as a voice for the oppressed and marginalized.

RELATED: Preview the PBS documentary “Fight the Power: How Hip Hop Changed the World”

Plus, Henderson shares a preview of the upcoming four-part “Fight the Power” documentary, premiering at 9 p.m. ET Jan. 31.

Full Transcript:

Stephen Henderson, Host, American Black Journal: Dr. Hasan Kwamie Jeffries, welcome to American Black Journal.

Dr. Hasan Jeffries, Associate Professor of History, The Ohio State University: Well, thank you very much. Great to be with you.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah, it’s great to have you here. So 50 years. Boy, that makes me feel a little old. I won’t say how much older I am than that. But let’s start with where that place is, Hip hop. I think there’s always a debate about when hip hop starts, when it kind of diverges from other forms of music. How do we pinpoint that 50 year anniversary?

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: Yeah. I mean, so hip hop’s chronological roots certainly need to be connected to the 1970s. That puts us into that half-century mark. But of course, as you well know, I mean, music is informed and influenced by that which comes before it. And with hip hop, we certainly see that made manifest in the use of sampling, for example. I mean, the throwback, the inheritance. But it is a unique form of Black cultural expression that is born in the post-civil rights post-Black power, really almost post disco age. And it is now, much to the chagrin of many doubters early on half a century old.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah, I mean, I can remember arguments and debates about whether this was music. I can remember arguments and debates about whether it was appropriate because of the lyrics. There were stations that said, we’re not doing that. We’re not doing this. Black stations that said, they wouldn’t play it. But white stations, I can remember these advertisements that would talk about what kind of music they did play. And then they would say, and no rap. It was instantly this kind of lightning rod for a cultural moment, really, I think, in our country that this was something so different. And what people, Black people, white people, what anybody was used to.

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: It was. And on one hand, it was something that was unique and different. It offered a critical biting commentary on them, on the times, especially when we move out of that sort of initial dance party, celebratory escape of art as escape music as escape in sort of the 1970s. So by the time we hit the early 1980s and the Reagan era and this cultural critique, political critique, economic critique. So it wasn’t just sort of the language and the use of words.

It wasn’t that it was just Black folk, although that always been a problem, they had always been a race music put off in the corner. But it was especially so because of the powerful and direct critique that rap music offered almost from the very beginning. That only gets more strident as we move through the 1980s, and we’re introduced to rap groups like N.W.A. And the critique of Police power and the War on Drugs.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah, and of course, all of this fits into the context of the importance of music in the movement, right? The civil rights and the advancement of Black people in this country has always had a soundtrack. And for the last 50 years, that soundtrack has been hip hop. But before that, there was always music sort of aligned with it and emanating from it and helping to shape that movement in important ways.

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: I know Stephen you’re spot on. Black folk have always produced music. They’ve always produced music with meaning and feeling and emotion, and it’s always been tied, as you said, to the revolution, the soundtrack of the revolution, whether that was all Negro spirituals or deep stirring gospel music, even into rock and roll and R&B.

When we think of dancing in the streets and some of the Motown songs that we think were just party music really had political messages buried with inside them to hip hop. So hip hop becomes a sort of a logical extension of the African American tradition of drawing on music to express opposition to the status quo. In addition to providing relief and escape from the woes of the day.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah. So let’s talk about this, this documentary that looks at this 50-year evolution. What’s fascinating to me is, again, I can remember the kind of early days of hip hop and rap in particular and how different the things that my children are listening to today are from that. It has come a really long way in just in terms of an art form.

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: Absolutely. Part of what is captured, I think, in the film is the evolution of the art form, not only in terms of the messaging but then also the production also, the commercialization. And so one of the things that’s pretty cool about the documentary is that you’re able to see these various influences over time so that by the time we get to the present, you’re kind of able to see, Oh, I see where a turn had occurred. I see where this moves from basement parties to corporate headquarters. I see where some of the political messaging was lost, but yet it’s still always, always there. Fifty years is not is a long time and the music isn’t static, just as the world that produces the music isn’t static.

Unknown Speaker 1: 2020 and the Black Lives Matter protests wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for hip hop.

Unknown Speaker 1: What am I?

Unknown Speaker 2: Culture informed and brought together generations of people from different backgrounds for this moment.

Unknown Speaker 1: My baby.

Unknown Speaker 2: Rappers have tried to highlight injustice in their art since day.

Unknown Speaker 3: 2020. It is very much a reflection of him. With us here at CNN. These are the issues. These are the problems. Hip-hop is a part of a movement of black music that started in slavery. There’s always this kind of protest in music.

Unknown Speaker 4: This music is culture.

Unknown Speaker 5: It did not look, sound, taste or smell like it does today were it not for history.

Stephen Henderson: When we think about the groups that exist now that are most carrying that message, I mean, it’s a much broader spectrum of art now than it was when it started. And there’s I mean, I think there’s some argument about whether some of it is too commercial or not Black enough or all these other things. But when you think of who’s carrying that message now and kind of at the core of that, who comes to mind?

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: Well, in the protest tradition, I think you have to look to Kendrick Lamar, for example, in terms of an artist who is more than just sort of underground, more than just, you know, somebody that Black folk listen to actually has popular appeal. But yet his music, you can turn it up in the car. You can play it in a club, but you can also just listen to it to hear the sounds of that protest tradition. And so he immediately, I think, jumps to mind, you know, thinking back to the Ferguson uprising. Of course, you know, everything is going to be all right. I mean, it becomes a chant, becomes an anthem, much in the tradition of “Fight the Power” back in 1989.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah. So, are we at a point where we have to worry about hip hop and worry about its future and the role it plays? I mean, as I said it in one way, it’s a good thing that it’s as ubiquitous as it is. I mean, I think much of American culture right now is shaped by hip hop, things that don’t have anything to do with music, things that have anything to do with Black people. But, you know, like with other things that come from our community that become mainstream, Do we have to worry about the ways in which we preserve its bare essence, the things that mean so much to us and carry us forward? Are we losing those?

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: You know, I think looking at the history of the music over the last 50 years tells us that organically hip hop is here to stay. Certainly, there is commercial crossover appeal. I remember. I’m sure you do too. Joking as a youngster like, oh, wouldn’t it be funny if you saw Big Daddy Kane or some of these early artists like rapping 50 years later, right, Like 40 years later. And now you know, their headliners are at the Super Bowl. So generationally it has had staying power.

But despite the commercialization, despite the crossover appeal, we still see generation after generation of young artists reflecting and carrying on that message of critique of society. And I think that’s because whether or not we’re here in the United States or even globally, because hip hop really has proven to be sort of the language of the oppressed, the language of the marginalized and artistic expression of those who are dissatisfied with the status quo that was its roots. And it continues to be, I think, the source of new blood and new energy, despite the commercialization sometimes of crass commercialization of the art form today.

Stephen Henderson: Yeah. So I’ve been waiting for a long time to talk to somebody about this. What do we do with Kanye? What do we do with someone like Kanye who look when he was younger and newer on the scene… I think everybody was really moved by the way he could put words together, the rhythm and all that sort of thing.

And of course, he’s produced so much of other people’s great, great contributions to hip hop. But boy, it’s really hard to know what to make of him now and what to make of him in the context of the movement. Right. The movement that hip hop is escorting through history. What do we do?

Dr. Hasan Jeffries: You know, it’s one of those questions that gets to the heart of any revolutionary movement. And I think we put hip hop… We need to put hip-hop in that particular context. You know, you create space for not just those who are going to further the revolution, but you create space for everyone. Now, that being said, I think it is important to recognize the artistic contributions and in many ways the artistic, creativity, and genius of somebody like Kanye West.

But that should not blind us from the problematic commentary, the problematic politics that he has embraced over the last five or six years or so. That needs to be critiqued by those outside of the hip-hop community, but also by those inside the hip-hop community. You don’t get a pass because you can drop a good beat. You need to be critiqued.

If you really begin to move away, I think from what hip hop really offered this nation as a gift. And he’s doing that not just in a way that is. I mean, it’s one thing if you just go commercial. It’s another thing if your politics then reflect this anti-Black, anti-democratic bias. That, to me, is especially problematic. And we shouldn’t shy away from critiquing that.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram @amblackjournal.

View Past Episodes >

Watch American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @amblackjournal.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*