Rise of Anti-Asian Hate Revives Asian American Civil Rights Movement Sparked by Vincent Chin’s Murder

Jun 16, 2022

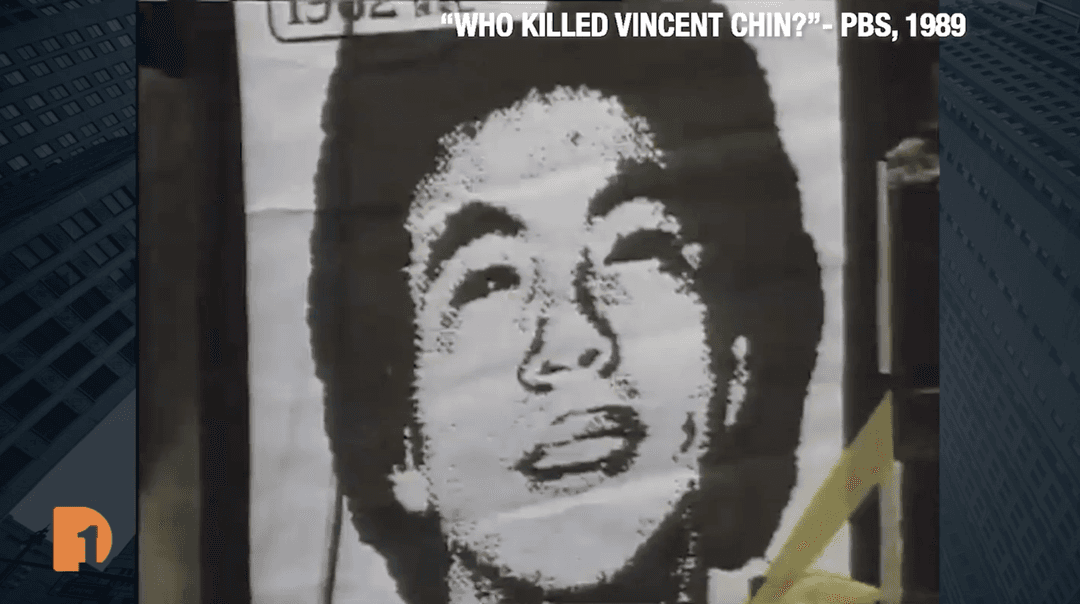

Nearly 40 years after the racially motivated murder of Chinese American Vincent Chin in Detroit, which sparked the modern Asian American civil rights movement, the hate crime is seeing a new light alongside a more recent rise in anti-Asian hate across the country; one that looks similar to Chin’s case, but some experts say is much worse.

Back in 1982, when Vincent Chin was murdered by two autoworkers, a wave of anti-Asian sentiment swept over Detroit and the nation as it was mired in recession and Detroit automakers were losing market share to Japanese car company Toyota. Today, the murder of Vincent Chin resonates with a new wave of anti-Asian hate, heard through rhetoric around the COVID-19 pandemic and seen in the tragic Atlanta spa shootings and other racially motivated killings that have targeted Asian Americans.

RELATED: Artist Anthony Lee Commissions New Vincent Chin Mural For Detroit’s Former Chinatown

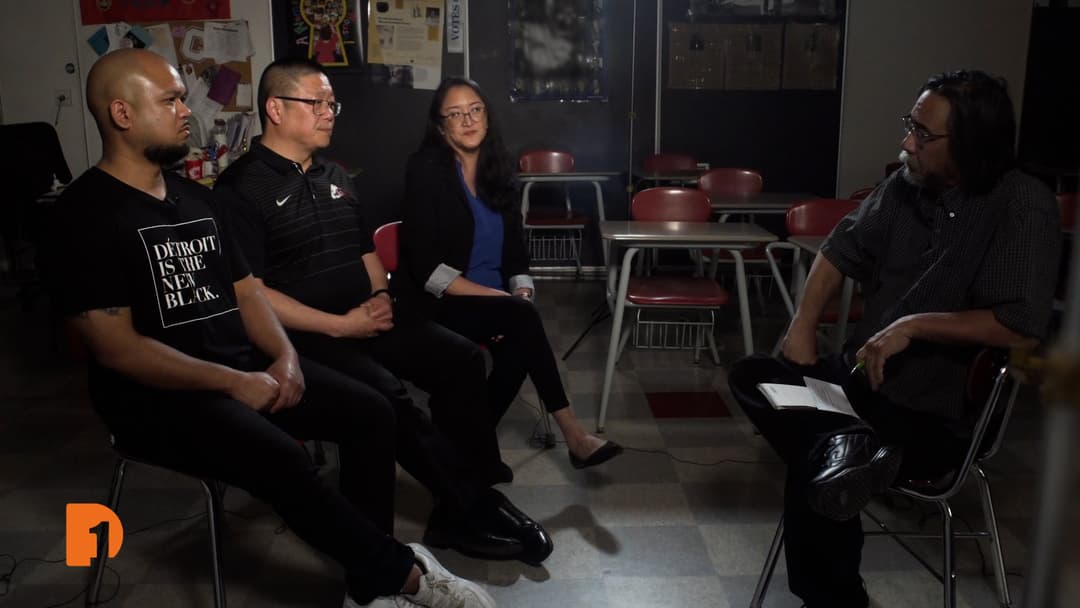

As the story of Vincent Chin’s murder sees a resurgence and connects to the continued anti-Asian hate still seen, One Detroit’s Senior Producer Bill Kubota explores how Vincent Chin’s legacy has shaped a new wave of Asian American civil rights activists. He talks with members of the American Citizens for Justice (ACJ), who began the fight for justice in Detroit as Chin’s case erupted into the national spotlight, and Asian American student activists from the University of Michigan about how Chin’s legacy informs their activism and advocacy for the Asian American community.

Then, Kubota talks with a few organizations — Whenever We’re Needed and Eastern Michigan University’s Healthy Asian Americans Project — about the work they’re doing to help, and he looks at the increasing population of Asian Americans in Michigan, including large communities of Bangladeshi and Burmese refugees and a new Chinatown forming in Madison Heights. Plus, he explores how Vincent Chin’s story is being used as a vehicle to educate K-12 students about Asian American history with State Senator Stephanie Chang, University of Michigan Asian American history professor Roland Hwang and ACJ activist Mary Kamidoi.

Full Transcript:

Bill Kubota, Senior Producer, One Detroit: In the eighties, the intent? Beat the Japanese car companies. Asian-Americans? Just collateral damage, you might say. It’s different now.

Bill Kubota: New Asians, more Michigan Asians, yet to learn about Vincent Chin, and what went on around here.

Arthur Park, American Citizens for Justice: I decided, well, I think I’ll buy a Toyota. This is in the eighties, right? .

TV Commercial: New car prices may never be lower, so now’s the time to buy.

Arthur Park: Cause it was cheap, and the same place that was selling Chevys, and Chryslers and things were selling Toyotas. So, I didn’t think much about it.

TV Commercial: See your Toyota dealer. He’s got what it takes.

Bill Kubota: The car ran fine. Until it didn’t. Arthur Park took it to a mechanic.

Arthur Park: You find out what’s wrong with my car? And he said, “Yes,” he said. I said, “What?” He said, “It’s shot.” “Oh. What do you mean?” “No, somebody shot it. Somebody shot the battery of your car.” So there’s some of that anti-Asian sentiment.

Bill Kubota: Arthur Park, Korean-American, joined Detroiters taking action for Vincent Chin. The group leading the fight? The American Citizens for Justice.

Asian-American activism, not a new thing, goes back to the 1960s, the Vietnam era. But mostly then it was a West Coast thing. Because that’s where most Asian Americans lived. Protesters, mostly draft age, being asked to go kill other Asians.

Frank Wu, President, Queens College, New York: It was young folks. What made the Vincent Chin case different is it brought together the first-generation immigrants, their American-born children. It brought together the Mandarin speaking and the Cantonese speaking. The Suburban and the inner city. It brought together Chinese-Americans and Japanese-Americans who knew, there it is again, you all look alike.

Bill Kubota: Frank Wu, president of New York’s Queens College, grew up in suburban Detroit.

Frank Wu: The Vietnam War was a raw wound. And if you had this color of skin, texture of hair, shape of eye, you had the look of the enemy. You had the look of the enemy from World War Two, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, from all of these conflicts that people remembered well.

Bill Kubota, One Detroit Vincent Chin’s death, less than a decade after the fall of Saigon. At the University of Michigan, they’re talking activism then and now.

Parker Woo, American Citizens for Justice I think the start of Asian-American studies, or a class in the American studies program. So those kind of gradually occurred later on in the 70s.

Bill Kubota: Parker Woo, campus activist. He joined the American Citizens for Justice. Living history, students today.

Victoria Minka, Student Activist: So I was already a sophomore in college when I was starting to become more aware of Asian-American history and activism.

Natalie Suh, Student Activist: Learning about Vincent Chin was one of my earliest experiences and exposure to any semblance of Asian-American history.

Victoria Minka: And I remember reading this poem about Vincent Chin and being wrecked by it. And going back to my mother asking, you know, “Why didn’t you tell me? Why don’t you tell me that this had happened? That it had happened so close to us?”

Natalie Suh: I would say the big turning point in my life when I realized there was Asian-American history, not only broadly, but specific to Southeast Michigan, specific to Detroit.

Victoria Minka: And so for this not to ever come up in the conversation, I was a little bit astounded. And I think that she was trying to protect me in a way.

Natalie Suh: When I asked my parents if they had heard of Vincent Chin, that my dad finally disclosed the instances of racism he faced as a Korean-American engineer in the auto industry. And the story he told me involved an exchange of words that was really akin to, “Because of you, MFs.” The infamous words from the Vincent Chen story.

Parker Woo: I think the younger generation needs to learn maybe certain things in the past. They need to learn the struggles that we went through as older activists and so forth. The kinds of difficulties that we had, trying to maintain people’s awareness, keeping information flows and things like that.

Helen Zia, Activist and Co-Founder, American Citizens for Justice Today, with 24 million Asian-Americans, it’s possible for, you know, Fujianese not talking to Mandarin, speaking people, not speaking to Cantonese, just within the Chinese-American community. Back then, it was very clear if we didn’t stand together, we wouldn’t have a voice.

Jim Shimoura, American Citizens for Justice The situation there was very bad, don’t get me wrong. I know that the unions would have these car bashing weeks. Pay a dollar, you took a sledgehammer, you could hit a Toyota. We were in a parking lot at a rally.

Jim Shimoura, Co-Founder, American Citizens for Justice But as bad as that was, I don’t think the atmosphere then was nearly as bad as it is right now. It wasn’t as pervasive as we have at this point. You’ve got a lot more attacks. You’ve got political figures and other people that are just legitimizing that kind of behavior.

Donald Trump, former U.S. President: Corona Virus. Kung flu. Yeah. Kung flu.

Jim Shimoura: It’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better. And I think we’re going through a very, very trying cycle. Social behavior and political dialogue between the trade war with China, COVID, and the fact you have this white nationalist movement running rampant.

Frank Wu: The Vincent Chin case was a precursor to everything that we’ve seen during the COVID 19 pandemic. When the violence first started to happen, you know, Asian-Americans would remark, “This isn’t new. It’s only the awareness of it that’s new.”

Bill Kubota, One Detroit Then it happened. In March last year, the Atlanta spa shootings, six Asian women gunned down, leading to perhaps the biggest Asian-American rally here since the Vincent Chin days.

Ceena Vang, Co-Founder, Whenever We’re Needed: And it was just an overwhelming number. Like, I did not think that that many people were going to be there. To be here, gathered today in unity. But unfortunately for such a devastating purpose.

Bill Kubota: Ceena Vang and her friend Zora Bowens led the rally, the first of a few around the city, rooted in the George Floyd protests the year before.

Ceena Vang: It was really nice to be able to bring so many people together that really cared about a cause. About stopping hate, and just unity in general. It was definitely a big first time for a lot of the older generation there, and it was nice to have them come out. Especially when the older Asians have been such a big target in all the hate crimes. I remember a lot of them coming up to us and just thanking us.

Bill Kubota: How do you keep this going, keep people together? Around here, different communities are dispersed across the region.

Detroit had a Chinatown once, its last vestiges seen in the film “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” By then, most of the Chinese had moved to the suburbs. Now, more Asians. A mosque in Warren, south Macomb County, just north of Detroit. Bangladeshis, the highest concentration of them in the U.S. outside of New York. They’re also on the east side of Detroit’s neighborhood called Banglatown.

And in Hamtramck, the once Polish enclave, surrounded by the big city. This vaccination clinic’s part of a program coordinated by Eastern Michigan University. Dr. Tsu-Yin Wu is connecting Asian Americans in a different way, by promoting better healthcare.

Dr. Tsu-Yin Wu, Healthy Asian Americans Project, Eastern Michigan University: As a Taiwanese-American. You know, I know that sometimes it’s not the best to be the smaller group. Because you get overlooked and people don’t know you even exist.

Dr. Tsu-Yin Wu, Healthy Asian Americans Project, Eastern Michigan University I feel like it’s my mission. I guess in the early days, I have some sort of a breast issue. And I was in my very early age of my life, and I feel like I was all alone, and I was in the doctoral program of nursing. And I should have all the solutions. If I have all those capabilities and I cannot do it myself, what about those people in the community who just came to the United States and do not have anyone to go to? I feel like, hey, you know, as a researcher, I need to find a way. I need to find a way to support especially the most underserved communities in Asian-Americans.

Bill Kubota, One Detroit Dr. Wu’s program operates across the state. In Battle Creek, southwest Michigan, a gathering at the Burma Center.

Peter Thwanghmung, Burmese Community Activist: If you look around today, all of us came from Burma. Most of us here, this room will be, you know, be almost empty if refugees didn’t come here. And refugee, to me, is a great thing. Because that’s freedom.

Par Mawi, Burmese American, Battle Creek I have a lot of experience, that, when I introduce myself that I’m from Burma, and they was like, “Burma? Where’s that country?”

Bill Kubota: Burma. Or call it Myanmar, by India and China. More than 3000 Burmese settled in Battle Creek now.

Peter Thwanghmung, Burmese Community Activist: It’s all based on social connection. So, we got, Battle Creek has been very accepting to immigrants like us.

Par Mawi, Burmese American, Battle Creek: So back in 2007, is, you know, we have a huge military coup.

Bill Kubota: Par Mawi, refugee. The keeper of Books, Stories, of Burma and Battle Creek. Last year she became a US citizen.

Par Mawi: And then I have no choice to living there, so I have to leave.

Peter Thwanghmung: We were discriminated based on our religion, and also for ethnicity. We’re a minority ethnic group in Burma. The Burmese here, they’re Chin people, mostly Christian, with their own culture of many in that country.

Par Mawi: They sent me to Houston, but, you know, it is a big city and I don’t think that I can survive there. So, I choose living in Battle Creek, because it’s here. It’s a huge Burmese community here. So we can help each other.

Christine Khim: Here in America, we just drive cars and we never move anymore. And then we just eat, and all the things that we eat don’t go anywhere.

Dr. Tsu-Yin Wu: Health is the priority, and the reason we are here today is diabetes. When these people come to this country, they have no insurance, they won’t go to see doctor. They don’t even think about doing any cancer screening like you have to do the colorectal or, you know, breast and mammography.

And the awareness, if we know that there is some groups out here: Burmese, Bangladesh, Nepali, Bhutanese, you know, smaller groups. And we can work each other, you know, support each other. And I think that’s very important.

Bill Kubota: Madison Heights, another mostly white working slash middle-class, inner ring Detroit suburb. But here, the past couple of decades, a change to this city.

Roslyn Grafstein, Mayor of Madison Heights: I think that Madison Heights, for quite a while, has been not just our Chinatown, it’s been our unofficial Asian town of Metro Detroit.

And then where we are here, which is John R., and just south of 14 Mile. This strip, this area, really is our unofficial Asian town of Madison Heights.

Kevin Chai, QQ Bakery: Usually when people want to come down, for Asian food they come to Madison Heights.

Bill Kubota: Kevin Chai works with his family at a Taiwanese bakery. Lots of specialty items, the most popular?

Kevin Chai: Probably the pork bun. It’s like the Chinese barbecue sauce, with the roast pork in it. It’s probably our most popular. There was a while where there was a lot of Chinese immigrants. I think mostly from just like mainland China. Probably come here for school work.

Bill Kubota, One Detroit Since then, more Asians from different places.

Kevin Chai: I’d say, about, a lot of Vietnamese, Filipino and Chinese.

Roslyn Grafstein: Just behind us, across the street that way is 168 Asian mart. It is the largest Asian Mart in the state. I mean, they have everything. Like attracts like. So we have Asian businesses who see that this is a really great place to be. They see how welcoming the city is, and they see the kind of business that they can get. That they’re going to get the foot traffic. So they’re just setting up around it.

Bill Kubota: Michigan’s Asian experience. How can you know if there’s no one to tell you?

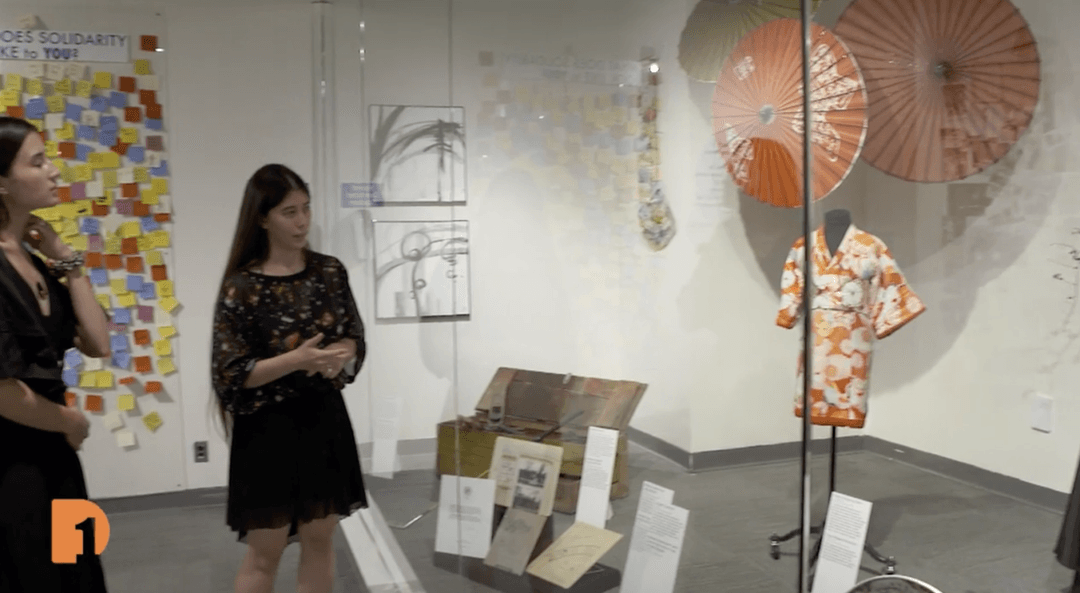

Mary Kamidoi, American Citizens for Justice: I just want some of these people to know the truth of what happened to us in World War Two, which was not right.

Bill Kubota: Mary Kamidoi, an American Citizens for Justice activist since the eighties, speaking to sixth graders at Detroit Prep. On the city’s Near-East Side.

Mary Kamidoi: My dad was one of 13 people that came to Kalamazoo, Michigan, to just get out and do something worthwhile. Even today, because when I go to middle schools, I have seventh and eighth graders ask me, “How can you speak English so well?”

I say, “Because I don’t know anything else to speak.”

“Oh, well how long have you been here?”

I say, “All my life.”

Bill Kubota: Kamidoi, in her early nineties, spent the war years incarcerated in an internment camp. Only because her parents came from Japan.

Mary Kamidoi: You know, even at an 11-year-old, I remember all of this. Thinking, “My goodness, they treated us like we were cattle.” But, you know, this is how we were treated at the time, when they were going to evacuate us out on our homes.

Bill Kubota: The last of a generation. Here’s history from someone who lived it.

Mary Kamidoi: You know, now that I’m older and all, and I’ve lived through it, and I’ve accepted a lot of it. But I haven’t forgotten a day of it.

Bill Kubota: Which brings us back to Vincent Chin, where Asian Americans and Michigan history intersect.

Stephanie Chang: It turns out that my dad was actually at one of the first rallies in 1983, but I don’t think I really had conversations with my parents about it until much later. Of course, learning about what happened to Vincent Chin, I think that sort of sparked a lot of my interest in wanting to work on civil rights issues and realizing that there was, you know, many, many issues going on that we need to continue to fight for.

Bill Kubota: State Senator Stephanie Chang has introduced a bill requiring Asian-American history in Michigan schools. Part of a package of laws covering other people’s history, too.

Stephanie Chang: So we have actually been pushing for our bills, which are about teaching not just Asian-American history, but Latino history, Indigenous history, Arab and Chaldean history, and Black history within all of our schools. Because we know that so many of our marginalized communities, we are not learning about that history precedent.

Bill Kubota: Lawyer and longtime American Citizens for Justice leader Roland Hwang teaches Asian-American issues at the University of Michigan. While some are getting it in college, he believes more needs to be done at the K-12 level.

Roland Hwang, Co-Founder, American Citizens for Justice: What students are getting are snippets of incidents. Whether it is the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War Two, and that may warrant a couple of paragraphs. Maybe a little bit about the Exclusion Act, but I doubt it.

So, really, there needs to be a more comprehensive understanding of the contributions and the trials and tribulations of the Asian-American community woven into U.S. History.

Bill Kubota: The Exclusion Act. The US barred the Chinese from our shores from 1882 to 1943, if you didn’t know.

Richard Mui, Social Studies Teacher, Canton High School: What I think led to the Vincent Chin attacks was really the same things that probably led to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Japanese-American internment, that it’s this other that is coming in and threatening our jobs and threatening our society.

Bill Kubota: At Canton High School, west of Detroit, students are getting more of this history because Richard Mui is there to teach it.

Richard Mui: I know in our district, in the high school level, it’s taught throughout the social studies. And that’s one of the benefits, I think. I share my resources with other teachers.

Stephanie Chang: But we know that our students deserve to know the truth about what’s happened in our country, both the painful parts, but also the contributions of communities of color.

Bill Kubota: The Asian-American history law could be like others enacted in Illinois and New Jersey. But with Michigan’s legislature controlled by Republicans, that’s unlikely any time soon.

Mary Kamidoi: Oh, well, you’re welcome, you’re welcome. I’m just hoping that you learned something from what I had to say.

Roland Hwang: When students are learning history, they should be able to see some of their own images in that history. Because otherwise it could be viewed as not relevant. You know, if I don’t see myself in that history, then I’m not a player in the community and in history.

Want to Know More About “Who Killed Vincent Chin?”

“Who Killed Vincent Chin?” will air on Detroit Public Television at 10 p.m. ET on June 20. Plus, four days of local and national events commemorating the 40th anniversary of Vincent Chin’s death will take place June 16-19. Check out One Detroit’s AAPI News & Stories coverage here.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to Detroit PBS YouTube Channel & Don’t miss American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram @amblackjournal.

View Past Episodes >

Watch American Black Journal on Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday at 9:30 a.m. on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*