Michigan’s returning citizens leverage prison work experiences to create new careers on the outside

May 4, 2023

For people who have been incarcerated, the road to reintegration into society can be long and challenging, especially when it comes to finding employment. Many employers remain reluctant to hire individuals with criminal records, which can create a significant barrier for those trying to rebuild their lives after serving time. This reluctance can create a vicious cycle, leading to recidivism and further incarceration.

RELATED: Returning citizens disproportionately locked out of Michigan’s workforce

RELATED: Watch One Detroit’s Future of Work town hall on returning citizens with Detroit Action

Despite these challenges, some returning citizens here in Michigan have found success in the outside world by leveraging the skills they learned in prison and finding ways to overcome the obstacles they face— but not all of them.

In a series of special Future of Work reports, One Detroit Senior Producer Bill Kubota and special correspondent Mario Bueno, a returning citizen himself, meet three other returning citizens to hear how they’ve found success through adversity.

Bueno talks with construction company owner Kimiko Uyeda, who served six years for filing a false police report; Kenneth Nixon, a Wayne State University student and Safe & Just Michigan employee who served 16 years after being wrongfully convicted for murder; and Aron Knall, a downriver barber who’s training for his barber’s license but had worked as a barber for nearly 30 years during his prison sentence.

Full Transcript:

Bill Kubota, Senior Producer, One Detroit: Working for a living, jobs. We talk a lot about that here on One Detroit, it’s the future of work. But for many people, people have done prison time, it can be quite a challenge getting a job. So, we turn now to Mario Bueno, our special correspondent, specially qualified to talk about this. Tell me about that, Mario.

Mario Bueno, Reporting for One Detroit: I served 19 years from the age of 16 for second-degree murder, going on my second master’s degree from Mike Ilitch School of Business. And even with that, it’s extremely challenging finding employment because of that felony.

Bill Kubota: So, then we hear from others in a situation like yours, call them ex-offenders, returning citizens, just plain felons. What is their future of work? Take a look.

Mario Bueno: We’re up north, Petoskey, with construction company owner Kim Uyeda in the midst of remodeling her own property. She scored a surplus bathroom countertop.

Kim Uyeda, Construction Company Owner, Served Six Years: I found it on the marketplace. Being a felon, I know how to mine my budget. $0.17 an hour in prison, you learn to do a lot with a little. So, for me in my line of work, it’s been great because I don’t advertise. All my work is word of mouth, and we’ve been able to employ myself and nine other people year-round. You know, just on word of mouth.

Mario Bueno: Uyeda, me, and others you’ll meet today, we’ve all done prison time. What were you charged with?

Kim Uyeda: Filing a false police report?

Mario Bueno: And what was the situation?

Kim Uyeda: So, at that time, I had been jumped outside of my home and I dialed 911 for an ambulance, and they sent the sheriff’s department. I was disoriented, didn’t know what was going on. When I got to the hospital, the officer was explaining to me what he said happened. And I was like, Wait a minute. So you’re saying I did this, so I did this?

Mario Bueno: Who was he?

Kim Uyeda: That was the officer that was in charge.

Mario Bueno: You said he was explaining what he thought had happened.

Kim Uyeda: Yes.

Mario Bueno: Uyeda says she knows who attacked her. Says the sheriff wasn’t buying it, that she hurt herself.

Kim Uyeda: And the next time I see him is later on that evening with an arrest warrant saying that I had confessed by stating that I did this.

Mario Bueno: Uyeda couldn’t remember what she told the officer. Meanwhile, the prosecutor added on even more charges based on her 911 phone call.

Kim Uyeda: I got six years.

Mario Bueno: Six years for filing a false police report.

Kim Uyeda: That’s correct. Because of the points system. Even though my felony was nine years prior, I still called the points for it because it has to be ten years before they dropped the points off.

Mario Bueno: The old felony? Writing a bad check. So, this used to be the closet for this room over here?

Kim Uyeda: It wasn’t even.

Mario Bueno: It wasn’t even? Oh, yeah. Because you built another wall. Her actual sentence, 6 to 20 years. A case study for those concerned about overly harsh sentencing. But we’re talking about how she’s hit a limit with her business, her work, her livelihood. When was the last time you actually made an attempt to get your contractor license?

Kim Uyeda: It was two years ago. Not only does it hurt me as a person who wants to be a contractor and not being able to take a larger contract, so there’s financially I’m kept down to the 70% range instead of 100% range, right? But I can’t employ as many people because I don’t have as big of a project that I can take on without a license. So, financially, it’s hurting the county, it’s hurting tax revenues, and it’s also hurting because I’m not training new people to do what I do. I’m already doing all of the work. So, the only thing I’m missing is this piece of paper.

Mario Bueno: Michigan licensing requirements are clear. A no-go for Uyeda.

Kim Uyeda: Filing a false police report, it’s considered fraud. So, then they say, “Oh, no, you’re a fraudster. No licensing.” The programming that you take within MDOC. So I took all the courses they had to offer in building trades. And they tell you, “Go take your test. You’ll get your builder’s license.” You’re teaching us a trade we can get licensed. We can only ever be a laborer.

Mario Bueno: They’re teaching us a trade for which we cannot get licensing.

Kim Uyeda: Because we are felons.

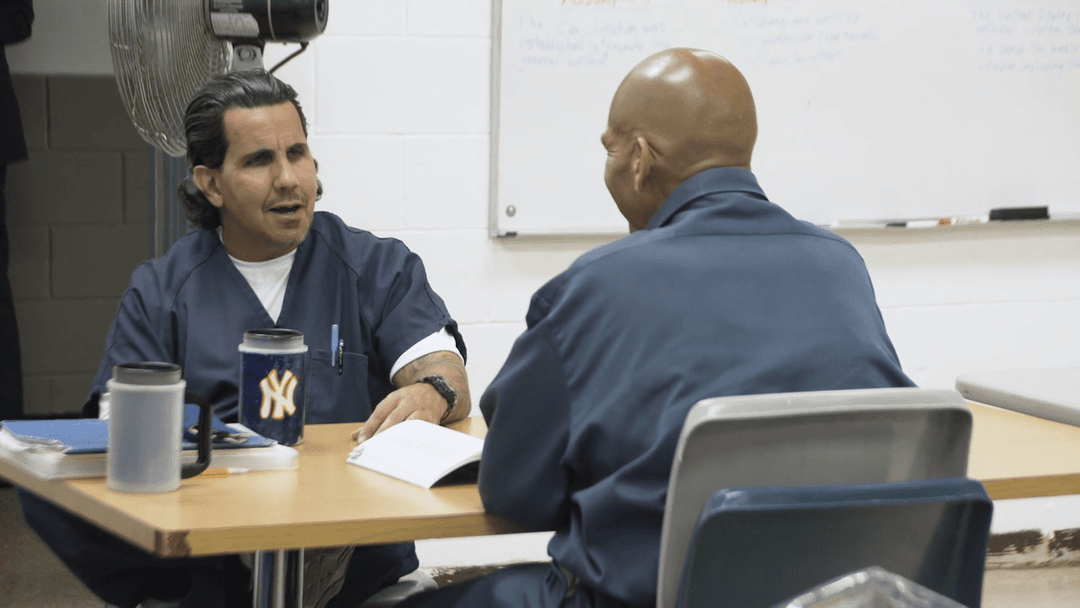

Mario Bueno: Kenneth Nixon is a Wayne State student and is employed with Safe & Just. He advocates for returning citizens. He’s networking at a symposium about just that at WSU. Your wrongful convictions, and then post-incarceration, how did that affect your employment opportunities?

Kenneth Nixon, Community Outreach, Safe & Just, Served 16 Years: It still affects me to this day.

Mario Bueno: And you’ve been home since when?

Kenneth Nixon: 2021.

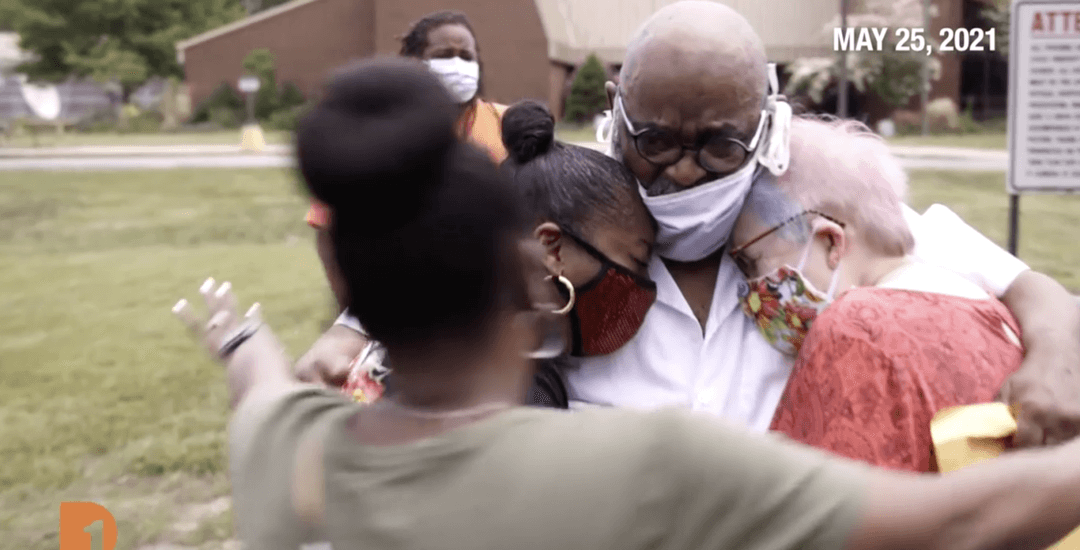

Mario Bueno: Nixon did 16 years. A double murder conviction overturned because of work by the Prosecutors Conviction Integrity Unit and the Cooley Law Innocence Project.

Kenneth Nixon: There’s a misconception that when you’re exonerated, your record gets expunged. That is not a true statement. There’s an entire legal process that has to take place, and it’s still on my record two years later. I applied for a big car company. I have a family member that’s a supervisor, has been a supervisor for decades there, gave me a referral and I go through the assessment process. I pass everything. I get a phone call from the background specialist and he says, “You failed the background check.” I’m like, How? After about five or 10 minutes of me trying to explain that this was clearly an error, the error also says that I’m serving a life sentence right now. So what do you think happened? I broke out of prison and apply for a job at your company.

Mario Bueno: Nixon did get another call back with a job offer, but he already found something else in which he’s very qualified. Having been trained in interpersonal skills behind bars, coupled with his life experience.

Kenneth Nixon: Elevating the message. I pride myself on being able to communicate effectively. But what happens to someone that’s not as communicative as I am and can’t explain the difficulties and perils of the system?

Mario Bueno: Here’s my old friend Aaron Law. He’s training for his barber’s license down the river in South Gate.

Aaron Knall, Barber in Training, Served 35 years: I taught myself and I worked as a prison barber for 25, 30 years.

Mario Bueno: 25 to 30 years.

Aaron Knall: Yes. And I really enjoyed it. I found something that I could do would help other people smile within a place like that.

Mario Bueno: Paroled after 35 years last fall. Knall went to an automotive aftermarket production plant and got the good news. I take pleasure in offering you a full-time position as a general laborer on first shift. So you’re– it’s not like you were just temporarily hired. You were hired full-time.

Aaron Knall: I actually got hired. I told them at the interview that I just got out of prison, etc., etc.

Mario Bueno: What was your crime?

Aaron Knall: Second-degree murder.

Mario Bueno: Second-degree murder?

Aaron Knall: Yes.

Mario Bueno: Knall went to prison at 15, 35 years ago. That first job out didn’t last very long. In one day you worked.

Aaron Knall: That’s the one day I worked.

Mario Bueno: Due to not meeting the requirements of the pre-employment background screening. Please turn in all your equipment.

Aaron Knall: She called me in the office, she actually asked me to reapply for the job in, like, a year. She said it was just too soon with me getting out. They said they watched me for a day, said that I was actually an excellent worker. I got along with everybody, but because of the history, they would have to let me go. That didn’t work out. I just said, Forget it. I’m going to school full-time. Came here and been going ever since.

Mario Bueno: You know, we have expectations before we come home. True or not true?

Aaron Knall: True.

Mario Bueno: And then life hits you, right? Life hits you with a brick.

Aaron Knall: Not with a brick with a boulder.

Mario Bueno: So, my point is, be honest, you cried, didn’t you?

Aaron Knall: Yeah, I cried in the car on the way home. I cried out of frustration. At what point would I be seen for who I am today opposed to the kid that committed my crime?

Mario Bueno: The common denominator for Aaron Knall, Kenneth Nixon, and Kim Uyeda, they gained valuable training in prison and were able to apply those skills while still incarcerated, like cutting hair, communication skills, and building trades. So this is 8,000 square feet.

Kim Uyeda: 8,000 square feet home. Yeah.

Mario Bueno: So, they were really prepared for the real world. The problem, so many others are not prepared and far more likely to return to prison.

Kim Uyeda: We’re becoming a society that has exiled people because of mistakes. Every one of us has made a mistake that could have landed us in prison. $99 check, anything over that is a felony in the state of Michigan. Two drinks and get in the car, that’s a felony in the state of Michigan. So, how easy, you know, every person that you talked to could have been in prison that easily.

Kenneth Nixon: The reality is we grow and we evolve. We grow out of, you know, negative mindsets. Science tells us that, evolution of life tells us that. No one is the same 20, 30 years later. Give people a chance. Give people an opportunity to prove that they are no longer the person that society judge them as decades ago.

Mario Bueno: Are you in a state of gratitude now that this all actually unraveled as it did?

Aaron Knall: Actually, I am. I look at it this way, one door closed and another one opened. The door that opened is where I’m actually supposed to be.

Mario Bueno: Aaron Knall, he still keeps that letter that told him he was fired close by.

Aaron Knall: I said, it’s their loss, not mine. And I look at that letter from time to time to keep myself grounded and keep myself motivated to do what’s right.

Bill Kubota: Mario, we’re working on more stories along these lines. Prisoner reentry. But what about you? What’s your future of work?

Mario Bueno: My accounting and tax firm, American Dream Accounting & Taxes, and hopefully continued collaborations with PBS, with you, Bill.

Bill Kubota: I think it’s going that way. Look for more stories along these lines here on One Detroit, talking about prisoner reentry and the future of work.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel & Don’t miss One Detroit Mondays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @DPTVOneDetroit, and Instagram @One.Detroit

View Past Episodes >

Watch One Detroit every Monday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. ET on Detroit Public TV on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*