Confusion at the polls: ProPublica reporters research solutions to fixing America’s voting system

Nov 3, 2022

One in five American adults struggles to read and write at an elementary level, so when it comes to citizens’ ability to register to vote and read a ballot, how do those with low literacy skills fare in the process? ProPublica reporters Annie Waldman and Aliyya Swaby recently explored the confusion and complexity behind America’s election process, how it impacts voters and what states can do to make the process more accessible.

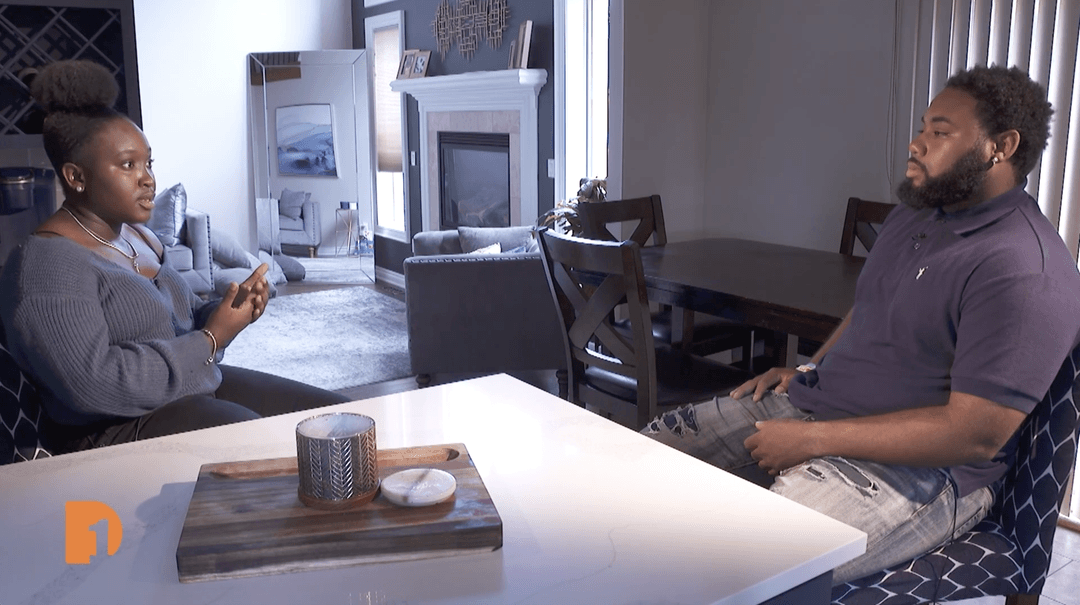

“The registration process is easy if you can read and write well, but if you don’t, that’s something that can be a roadblock, and that’s just the first step in the process. It can block you from voting at all.” Swaby told One Detroit producer Will Glover in an interview.

RELATED: How to Fix America’s Confusing Voting System

Glover sits down with Swaby and Waldman to look at the history of discrimination against voters with low literacy skills, with nationwide literacy tests in place until 1965, and the current challenges voters face when trying to participate in our democracy. They talk about the importance of good ballot designs and language, and how poorly created ballots can shape the outcome of an election.

Plus, they discuss the barriers states face in changing ballot design to make the process more accessible and equitable, and they share where America sits in comparison to other countries based on the complexity of our election process.

This story coincides with One Detroit’s 1-hour election special episode with the Detroit Free Press. Watch “Beyond the Ballot Box: A One Detroit Election Special with the Detroit Free Press” on-demand now.

Full Transcript:

Will Glover, Producer, One Detroit: Aliyya, let’s start with you. Were you surprised at all that this is where reporting on a confusing voting system took you or was this the target?

Aliyya Swaby, Reporter, ProPublica: So we started looking at this because of the statistic that one in five American adults struggles to read at a basic level. So we started from the literacy portion and then decided to look at what does that mean for our country at large? Not just for those individuals who struggle to read, but we’re looking at our democracy. What does that actually mean for us?

So we then started following the threads of our nation’s history. Obviously, there were literacy tests up to 1965 that prevented certain people from being able to vote. And we wanted to see what are the current challenges in the voting process that impact those people.

I think when we looked at the fact that it was so challenging for people who struggled to read, we were surprised. It’s easy to take for granted things in the process that if you are able to read well that you don’t struggle with like the registration process is easy if you can read and write well, but if you don’t, that’s something that can be a roadblock. And that’s just the first step in the process. So it can block you from voting at all.

Will Glover: The woman we’re focusing on, Faye Combs. Annie, just give us a little bit of insight into how her trouble with reading was impacting her real life, where the pen meets the paper in the ballot box.

Annie Waldman, Reporter, ProPublica: So I think one of the most surprising things of this story was, as Aliyya was just saying, how many people this impacts. It impacts 20% of the population who really struggle with reading and don’t necessarily have the wide range of foundational abilities to help them get a driver’s license or help them at the voting booth. Faye Combs was one of those individuals.

Faye kept it a secret that she struggled to read up until her forties. She kept it from her husband. She kept it from her children. When she would vote, eventually she did tell her husband, she would rely on him to help her through the process, often having him guide her, helping her read the ballot.

She would get really nervous when she would go into the voting booth on her own, seeing the people coming in and out of the booth next to her so quickly while she was still struggling to kind of get through each part of the ballot. Later on, she got a tutor, she learned to read, and she overcame this. And she really sees it as her mission to help other people, not only to reduce the stigma so that they can get the appropriate foundational help that they need to read better, but also to get them out to the polls to vote which is so important for our democracy.

Will Glover: What about the design of the ballots and the registration forms changes outcomes of entire elections?

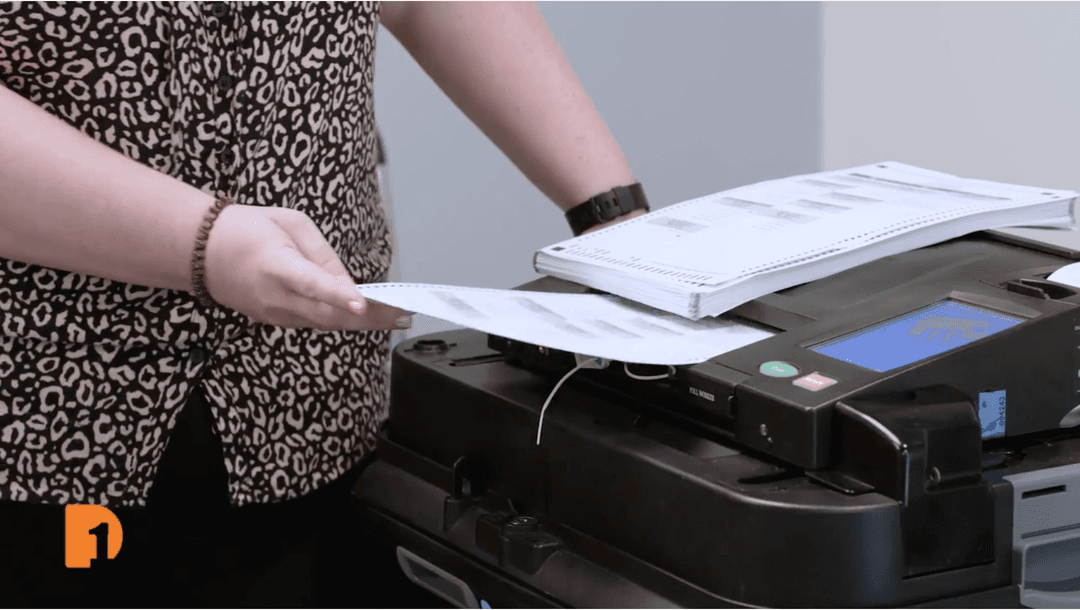

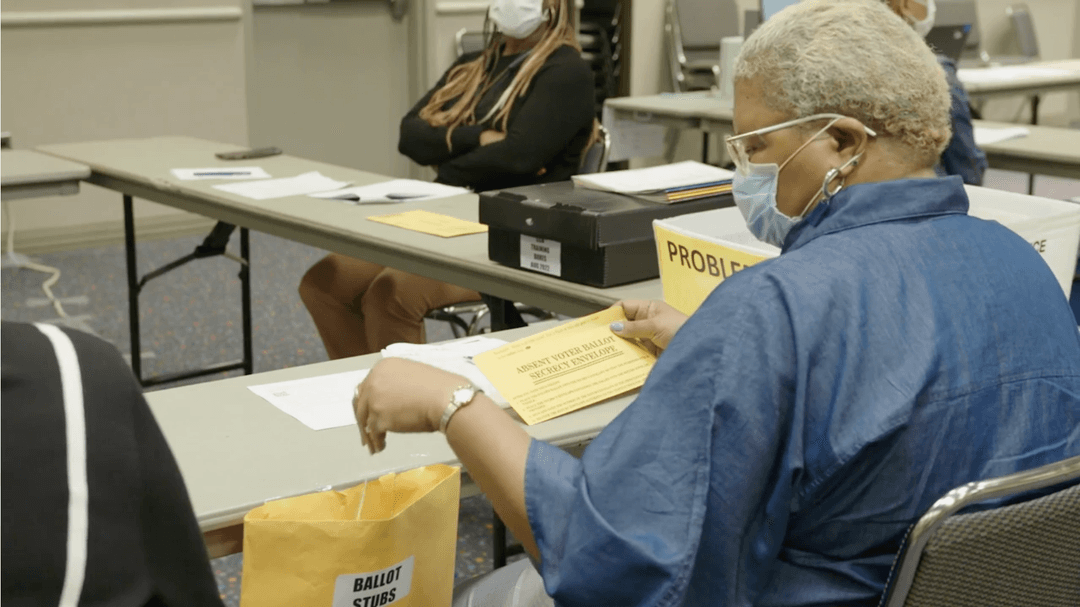

Aliyya Swaby: We talked to one expert and this quote really sticks with me as I think about the design, who said that she in her research saw people… Instead of reading the ballot from column to column, they would try and read it all the way across. So something as simple as that. When you don’t have clear markings showing people how to read a ballot, even that can result in people voting for someone they don’t want to vote for or incorrectly filling out the ballot and potentially risking having their vote thrown out altogether.

We were able to collect several examples from different lawsuits and different organizations, including the Center for Civic Design. That’s really the main organization that works on helping states and municipalities to redesign their ballots. There were numerous examples of comparing states before and after they ended up simplifying their ballots.

Often that was reducing the text on the ballot. It was sometimes putting a red X where the signatures should go so that people didn’t forget to or miss the spot that they were supposed to sign and risk their vote being thrown out altogether. Sometimes it was the column that they were supposed to fill out being in a place that they would look for it. So that happened in the Broward County election in Florida where the column cut off or wasn’t in a spot that was easily visible. So A lot of people skipped that election altogether.

Will Glover: When states are approaching this design of how their ballots are, are there any challenges to that? Is there any reason why states wouldn’t want to make sure that their citizens have the best ability, through ballot design or registration design, to participate? What are the barriers to states being able to make this a more accessible thing?

Annie Waldman: That’s a great question. So some of the barriers that we’ve come up with is, you know, money. I mean, it costs money to change election ballots. It costs money and time to revamp a whole system. But there are a lot of committed individuals who work for elections offices out there, regardless of their partisan leanings, who do believe that making these forms more accessible is incredibly important to increasing the electorate.

One thing I will say is that when it’s election experts who are making the decisions, they often make decisions that are in the interest of voters. But that’s not always the case with politicians, right? So even though people are making changes toward redesigning the ballot and making it more accessible in various places, when it comes to redesigning the process or changing the registration to make it more accessible, they’re not always doing that.

The United States stands out among its international peers as having an incredibly convoluted and complicated election process from the beginning. Right when you have registration of voters, the United States doesn’t have an automatic registration program in place that as soon as you get your driver’s license, everybody is kind of looped into the registration system. Some states are starting to do that. And where you’re seeing states make these changes, by having automatic registration or same-day voter registration, you see an increase in turnout and successful votes.

So that’s really in the hands of the politicians and the legislators. It’s not always in the hands of elections experts or people down on the lower end of the power spectrum. But if politicians do have a commitment toward accessibility, toward democracy, they will make this process more accessible from registration to the ballot box.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel & Don’t miss One Detroit Mondays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @DPTVOneDetroit, and Instagram @One.Detroit

View Past Episodes >

Watch One Detroit every Monday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. ET on Detroit Public TV on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*