Will Detroit’s I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project restore a once thriving Black corridor in the city?

Jul 14, 2023

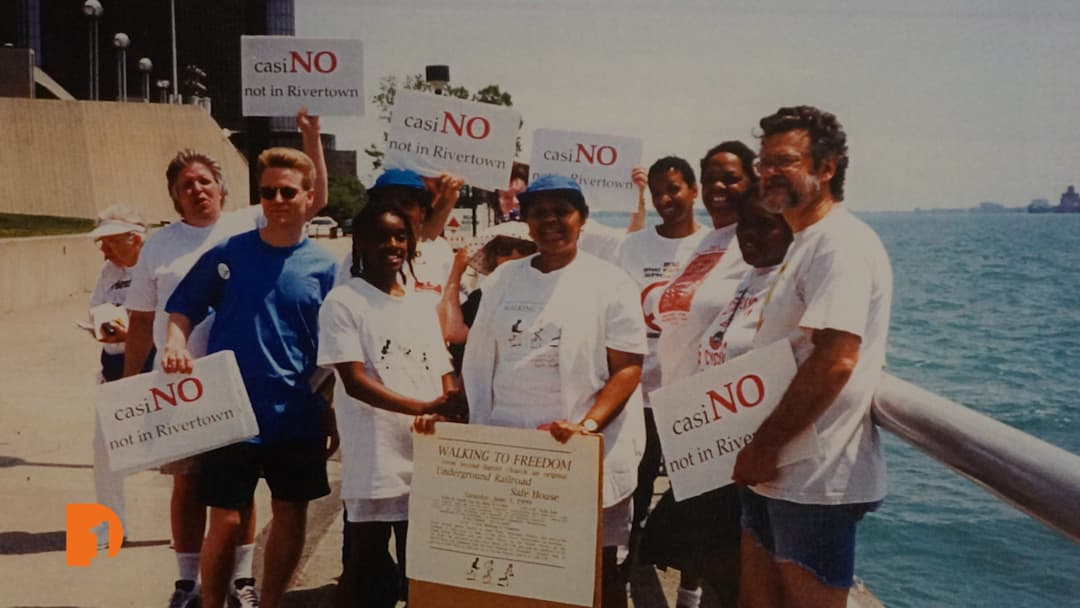

Detroit’s Interstate 375: It’s considered to be the shortest highway in the country, stretching just over one mile long, and when it was constructed, it led to the destruction of two thriving African American communities, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, in the city. Now, state and city officials have plans to redevelop the highway into a more traversable boulevard, but will the redevelopment efforts be able to return what was once there?

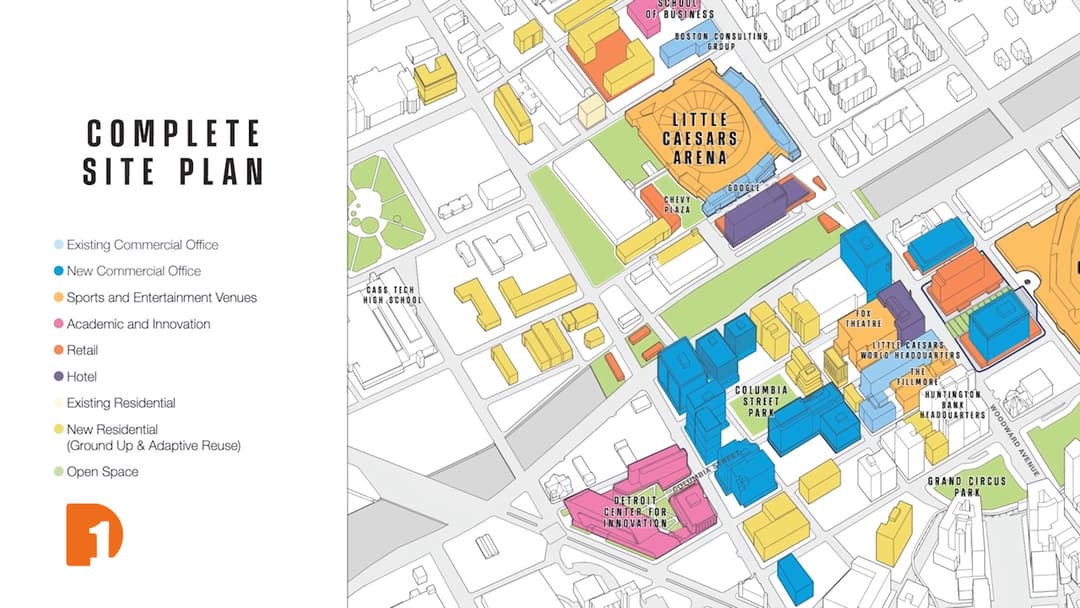

Current plans for the highway’s removal are slated to begin in 2025, after federal officials approved a $104.6 million grant just before the new year to speed up the process. Six lanes of street-level boulevard with wide sidewalks and bike lanes will be added in the highway’s place, and the roadway will narrow to 4 lanes as it approaches the Detroit Riverwalk. Approximately 25-31 acres of land will also become available for development.

BridgeDetroit reporter Jena Brooker, who has been following MDOT’s I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project closely, teams up with One Detroit producer Will Glover to break down the project’s goals and how members of the community are reacting to the plans.

Brooker talks with freelance urban planner Paul Jones III, chair for the Detroit City Planning Commission Lauren Hood, and Detroit Greenway Coalition Executive Director Todd Scott about MDOT’s redevelopment plans, the racial history embedded into the highway’s story, and whether they believe the plans will achieve what state and city officials have said it will.

Full Transcript:

Jena Brooker, Reporter, BridgeDetroit: I-375, the highway that destroyed a thriving epicenter of Black life in Detroit is going to be filled in and replaced by a six-lane street-level boulevard with bike lanes and wide sidewalks. Once filled in, approximately 30 acres of prime real estate will open up. Last year, the city began hosting monthly meetings with stakeholders and community members about the process. Federal and state officials say the boulevard will reconnect the community destroyed by the highway and be a reparative process. But various community members have concerns ranging from the physical design to if the process will really be reparative.

Paul Jones III, Freelance Urban Planner: I think we’ve all kind of swayed around with the idea of getting rid of 375 for a long time. The fact that this is happening in a way now, I think is both exciting, but also it makes me a little anxious because at all I don’t know that all the things have aligned here to make this project as transformational as it should be.

Jena Brooker: At a February meeting, more than 50 residents and stakeholders shared their thoughts on the project. Some already feel like it isn’t properly centering equity injustice.

Lauren Hood, Chair, Detroit City Planning Commission: As urban planning practitioners, you’re not required to have a social justice background or a critical consciousness about race. So it should be no surprise that when we get to projects like this, there’s a whole line of thinking that isn’t included because those people aren’t trained with that. So is it their fault? I don’t know where the problem needs to be addressed, but it’s a recurring theme, especially in cities like Detroit, where our community development and urban planning is so deeply intertwined with race and justice.

Jena Brooker: An analysis was done of the intergenerational wealth lost when a highway similarly displaced a Black community in Saint Paul, Minnesota at the same time Detroit’s highway went in. The analysis found that at least $270 million of intergenerational wealth was lost. So given that and that history, do you think that it’s possible that this project could actually be reparative?

Lauren Hood: It can be again because I feel like those technicians that are leading this charge are open to receiving different kinds of ideas. I think you have to make a data-driven case, though. I used to think in racial justice work you could appeal to people’s moral compass, their empathy; that ain’t going to do anything. You need to make a data-driven case for those folks to behave differently and I think it’s possible.

Jena Brooker: Others have critiques of the physical design of the boulevard, that the state is prioritizing traffic over connectivity, pedestrians, and safety. With nine lanes at some points, it’s wide and replicates the effect of a highway. So can you touch on that? Do you think that it will lessen the divide that the highway currently creates between the neighborhoods?

Todd Scott, Executive Director, Detroit Greenways Coalition: In some ways, yes. In other ways, we still have some concerns. I’d say one of the biggest benefits is going to have is the reconnection of downtown to Eastern Market. Because right now I often say that if you’re in downtown and someone asks you for directions to Eastern Market by bike or walking, it’s basically, no one really knows.

Jena Brooker: According to Todd Scott of the Detroit Greenways Coalition, there will be a nice connection from Ford Field to Eastern Market. And during off-peak traffic hours, it should be more pedestrian and biking-friendly. So what do you think of the current redesign of the highway right now? And what would you want it to look like?

Paul Jones III: I would want it to look very different. So I would say, it’s not a smart design, it’s not an urban- it’s not a design that really lends itself to any level of vibrance, urban vitality, and density. In a lot of ways, the road design that they presented would be more dangerous for pedestrians than the current configuration as a freeway.

Jena Brooker: Paul Jones III, freelance urban planner, remains skeptical of transportation leaders pointing to the Woodward Avenue Q-Line project that left many Detroiters disappointed. What are some of the things that are realistic to come out of this project that could be reparative?

Lauren Hood: I’ve heard folks talking about land trust. I think that could be interesting. So there are supposed to be 31 acres of developable land that are a result of the highway resurfacing. It would be great if we could figure out how Detroiters could financially benefit from that.

People are also talking about, could we have a Black business corridor in honor of the Black businesses that were destroyed in Black Bottom/Paradise Valley. That’s a thing. I really would like to hear what ideas citizens have. I think planners like to talk to planners. I want to hear what people that are differently oriented have to say. I want to hear what artists- We just need some more creative thinkers on what is possible.

Todd Scott: I think the most important thing is that you have a facility where you can bike or walk without a lot of delays. And when that happens and you increase bike-ability and walkability, you can go much further for the same amount of time. What we don’t want to do is have a facility where you have to stop every block, push a button, and wait a minute or two to get a walk signal to continue on, because it’s going to take you a long time to get anywhere. And so, I mean, on paper, those plans look like you’re connecting things but given the amount of delay they can introduce to people walking and biking, they’re really not connecting with them.

Jena Brooker: The highway is expected to be removed by 2027. Until then, state officials are hosting monthly meetings with community members and stakeholders to get input on the design and the process. Despite stakeholder requests to reduce the width of the boulevard at every step of the project, state officials have noted that they will not do so. One major decision that is still up in the air though, is who gets the 30 acres of land that will open up valued at $50 million. This decision and more will shape if the project can really address the harm caused by the highway.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel & Don’t miss One Detroit Mondays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @DPTVOneDetroit, and Instagram @One.Detroit

View Past Episodes >

Watch One Detroit every Monday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. ET on Detroit Public TV on Detroit Public TV, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*